OCCA’s Aquatic Invasive Species Guide

Invasive Plants

-

![Water Chestnut floating in water]()

Water Chestnut

The water chestnut has a stem which extends to the surface of the water and ends in a rosette of floating, saw-toothed leaves. The plant bears a spiky fruit, which can pierce tennis shoes and thick-soled boots. In addition, water chestnuts can clog pipes, canals and waterways and adversely affect the environment by removing oxygen from the water and out competing native vegetation. OCCA has spearheaded a manual eradication effort of the water chestnut on Goodyear Lake.

Best Management Practices

The best way to deal with water chestnut is by hand pulling all visible plants, making sure to include the roots as well. This is best done before June when the plants begin flowering and producing nutlets. For large infestations, mechanical harvest is best. Nutlets can persist in the substrate for up to 5 years and can be transported by waterfowl and geese, so continued monitoring and periodic removals are necessary.

-

![White flowers with yellow centers floating on dark water surrounded by green lily pads.]()

European Frog Bit

A free-floating plant of still and slow moving waters, European frog-bit can quickly form dense mats that block sunlight and alter aquatic ecosystems. European frog-bit can be recognized by its round or heart-shaped, leathery green leaves, which are just 1-2″ across. Rosettes of leaves arise from a node on an underwater runner called a stolon. Stolons can grow to several feet long and have multiple rosettes arising from them. In mid-summer, the plant produces small flowers with three white petals surrounding a yellow center. In late summer, the plant produces vegetative buds called turions that fall to the bottom and produce new plants the following year.

Best Management Practices

For more heavily infested water bodies it is suggested to harvest near launches to help prevent its spread. Herbicidal options are available, but the treatment of severe infestations is usually ineffective and expensive.

-

Yellow Floating Heart

The name of the yellow floating heart is deceivingly charming. It has round, floating yellow flowers that may look similar to heart shapes, and they can sometimes be mistaken for water lilies, another aquatic plant that bears flowers. The Yellow Floating Heart is a bottom-rooted, aquatic perennial that can place significant pressure on the ecosystems that it invades by crowding out indigenous plants and altering the chemical composition of the water. It can produce dense mats of leaves in the form of a floating canopy, which results in reduced flow, reduced light penetration, lower oxygen levels, and altered nutrient cycling of waterways. Yellow floating heart prefers slow-moving rivers, lakes, and reservoirs.

The Yellow Floating Heart, originally from parts of Europe and Asia, has spread to North America due to its visual appeal. However, its invasion can have serious consequences. The plant's dense mats can impede recreational activities such as swimming or boating, making it a significant concern for water enthusiasts.

-

![]()

Yellow Flag Iris

Yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus) is an invasive ornamental perennial plant that is native to Europe, western Asia, and northwest Africa. It grows 2 to 3 feet tall in shallow water or mud along the shores of temperate wetlands, lakes, and slow-moving rivers. Flowers are pale to dark yellow with brownish-purple mottled markings, and leaves are flat and sword-shaped. It can produce many seeds that float from the parent plant, or it can spread via rhizome fragments. Once established, it forms dense clumps or floating mats that can alter wildlife habitat and species diversity. All parts of the plant are poisonous, causing livestock to become sick if ingested and resulting in lowered wildlife food sources. Contact with its resins can cause skin irritation in humans. Dense areas of this plant may also alter hydrology by trapping sediment.

Management

Populations of yellow flag iris can be managed by mechanical or manual removal, which involves cutting and digging up rhizomes. If pulling or digging, care should be used to protect the skin from irritating resins. Because rhizome fragments can form new plants, all rhizome fragments must be carefully removed. Covering the plants with tarps and chemical control are other options for management. Large populations should be managed by licensed applicators for aquatic herbicides, as chemicals can impact aquatic wildlife if not properly administered

-

![]()

Eurasian watermilfoil

Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) is a submerged, rooted plant native to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa that was first found in the United States in the 1880s. It typically grows 3 to 10 feet long, with feather-like leaves divided into 12 or more pairs of thin leaflets. Leaves are arranged around the stem in whorls (groups) of 4. Invasive milfoil can be distinguished from its native lookalikes by counting the pairs of leaflets. Native milfoils will have ten or fewer pairs of leaflets. The stems and leaves of Eurasian watermilfoil tend to be limp when taken out of water, while native milfoils have stiffer stems and leaves. Eurasian watermilfoil can reproduce via fragmentation, meaning a single stem fragment introduced to a waterbody can take root and establish a new population, making the plant very easy to spread. In dense populations, Eurasian watermilfoil forms dense, floating mats of vegetation on the surface, preventing light penetration for native aquatic plants below the surface. Dense mats also impede watercraft navigation, often clogging boat motors and getting tangled in propellers. It also reduces the quality of habitat for fish and invertebrates.

Management

The best way to manage Eurasian watermilfoil is to prevent its establishment. Watercraft should be inspected and all plants, plant fragments, and animals should be removed from boats and equipment. Drain all water from boats and equipment, and clean the boat with a potassium chloride solution (KCl), spray with high-pressure hot water, or allow the boat and equipment to dry out of water for at least five days. Chemical treatments can be used, but research has shown that treatments used to control Eurasian watermilfoil can be more harmful to native plant communities than the presence of Eurasian watermilfoil itself. Mechanical and manual harvesting can provide temporary Eurasian watermilfoil control to help mitigate recreational and navigational impacts.

Photo: Sarah Coney, CRISP -

![Curley-Leaf Pondweed]()

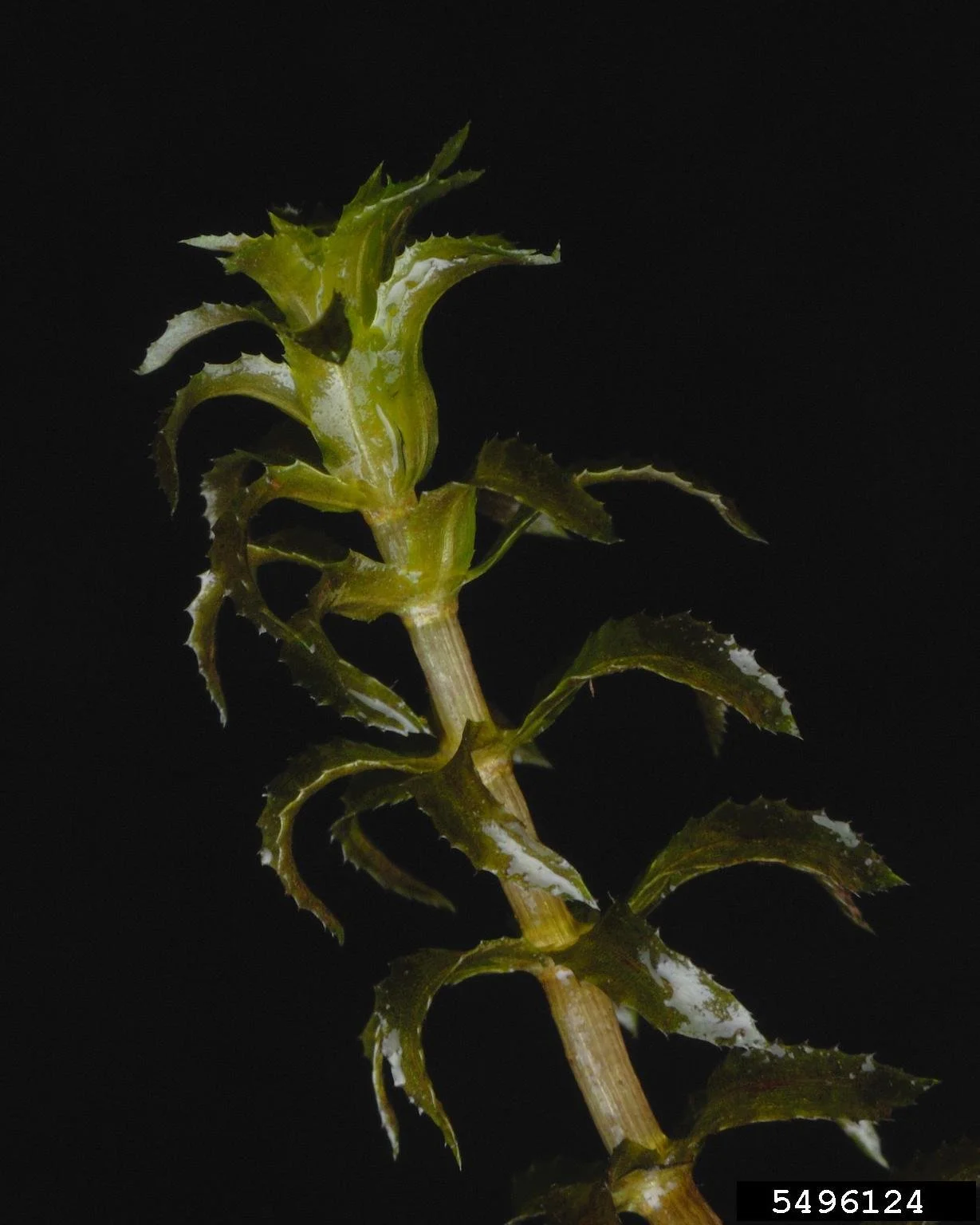

Curley-Leaf Pondweed

Curly-leaf pondweed (Potamogeton crispus), also known as crisp-leaved pondweed or curly pondweed, is native to Eurasia, Africa, and Australia and was introduced to the United States in the mid-1800s. Its leaves are oblong and attached to the stem in an alternate pattern. Leaf margins are wavy, resembling lasagna noodles, with fine teeth all along the leaf margins. In the mid-summer, curly-leaf pondweed begins producing winter buds, called turions, which remain dormant in the soil and germinate the following spring.Turions are an important reproductive agent for curly-leaf pondweed, with some curly-leaf pondweed beds containing up to 1600 turions per square yard. During early spring-summer growth, the plants can form dense monocultures which cover large areas of the water surface. These dense monocultures can restrict water-based recreation like fishing, boating, and swimming and crowd out native aquatic plants. After turion production, mass die-backs of the plant increase the nutrient load in the water column which can subsequently lead to harmful algal blooms and oxygen-depleted water.

Management

The best way to keep a lake free of curly-leaf pondweed is to prevent its establishment by practicing the “Clean, Drain, Dry” protocol on all watercraft and gear. Mechanical harvesting will not fully eradicate curly-leaf pondweed due to the turions in the sediment, but it can help mitigate recreational and navigational impediments for a single season. Harvesting can also remove plant biomass, and thus phosphorus, from the waterbody, which can help reduce the likelihood of harmful algal blooms and dissolved oxygen depletion. Chemical management requires multiple years of early season applications to deplete the turion bank in the sediment, which can be expensive and may not be a viable long-term solution. Die-back from chemical applications can also cause phosphorus release into the water column. Chemical treatments should be conducted in the spring when plant biomass is low to help minimize nutrient release.

Photo: Turion - Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut, Bugwood.org -

![]()

Hydrilla

Hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata), often called the “world’s worst invasive aquatic plant,” is an aquatic plant from southeast Asia that was first introduced to the United States in the 1950s and has since spread to many states throughout the country. It grows along the bottoms of rivers, lakes, streams, wetlands, and ponds. Plants have many branches with each individual branch having a series of whorls, each with 4-8 slightly toothed leaves. It can be distinguished from native elodea by counting the leaves on a whorl. Native elodea has whorls of three leaves that have smooth edges and smooth mid-veins. It reproduces by seed, overwintering buds called turions, and tubers that grow at the end of the roots. New populations can sprout from any of these, as well as plant fragments that easily break off from the main plant. Infestations can have negative impacts on recreation, tourism, and aquatic ecosystems. Dense mats of hydrilla can shade out and displace native plants that provide food and shelter to native wildlife. Infestations can decrease dissolved oxygen in the water, resulting in fish kills. It also interferes with waterfowl feeding areas and fish spawning sites, and dense populations can be very difficult to navigate in watercraft.

Management

The best way to prevent hydrilla invasion is to clean, drain, and dry all watercraft. Watercraft should be inspected and all plants, plant fragments, and animals should be removed from boats and equipment. Drain all water from boats and equipment, and clean the boat with a potassium chloride solution (KCl), spray with high-pressure hot water, or allow the boat and equipment to dry out of water for at least five days. Mechanical removal of hydrilla requires specialized machines, which can be very expensive. Up to six harvests may be required annually due to the rapid growth rate of hydrilla. Mechanical removal is typically only used in areas close to water supply intakes or when immediate removal is necessary.

Photo: Stem - Tim Krynak, Cleveland Metroparks, Bugwood.org

Invasive Organisms

-

![Close-up of numerous seashells packed together.]()

Zebra Mussels

In summer 2007, Otsego Lake was invaded by the zebra mussel – whose ill effects include ecological destabilization, damage to municipal, residential, and commercial intake pipes, production of sharp shells causing injury to recreational users of the lake, and emission of unpleasant odors. Once established, elimination of this mollusk is impossible, making control the best option.

-

![]()

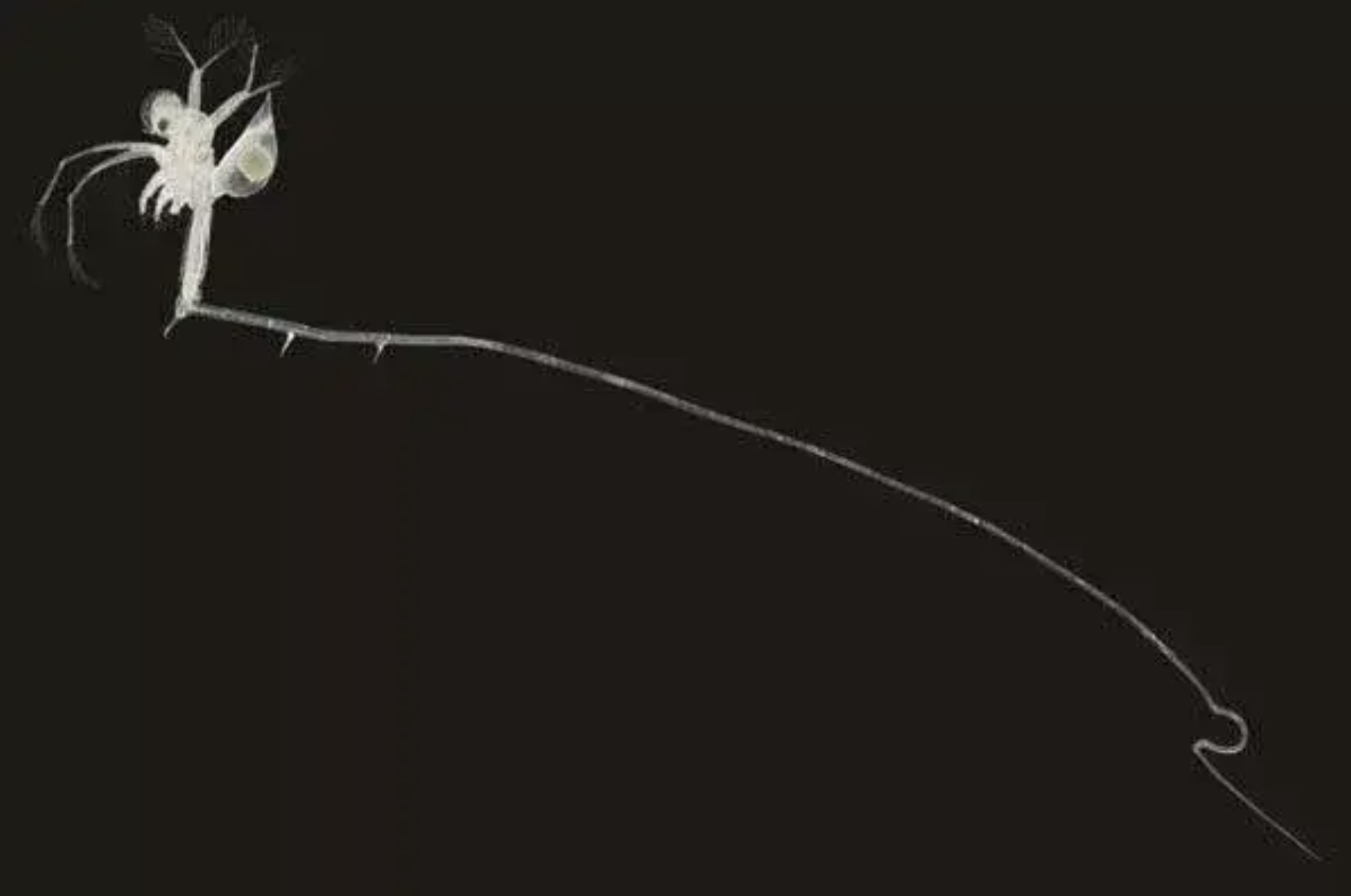

Fishhook Water Flea

The fishhook water flea is an aggressive, predatory crustacean that gathers in large numbers. It can foul fishing lines, downrigger cables, and fishing nets. This flea feeds on smaller zooplankton, and its impact on ecosystems is not yet fully understood. The fishhook water flea and its relative, the spiny water flea, are easily spread through boats and fishing gear. They can reproduce asexually, allowing just a few individuals to quickly build a large population.

The fishhook water flea has a small, translucent body with black eyes. Its most distinguishing feature is its long, slender tail, which has three barbs and a characteristic S-shaped hook at the end. Clusters of fishhook water fleas can resemble wet cotton when seen on ropes or equipment.

The fishhook water flea was first discovered in the United States in Lake Ontario in 1998. Since then, it has spread to several inland lakes. Recently, it was found in the Pepacton Reservoir and has also been reported in various Finger Lakes.

Prevention Tip: Both the spiny water flea and the fishhook water flea can easily be transported on boats, fishing equipment, and bait wells. Always follow clean, drain, and treat (or dry) practices to help prevent their spread.

Photo: Igor Grigorovich, University of Windsor -

![]()

Quagga Mussels

The quagga mussel (Dreissena rostriformis bugensis) is a species of invasive mussel that is native to Ukraine and was first introduced to the Great Lakes in the late 1980s, likely via ballast water in European ships. Its shell is generally black, yellow, and/or zig-zagged. The quagga mussel resembles the zebra mussel, but can be distinguished from the zebra mussel because it is paler toward the end of its hinge. It is also slightly larger than the zebra mussel. The quagga mussel breeds prolifically, with fully mature females capable of producing up to one million eggs per year. Where quagga and zebra mussels co-exist, quagga mussels appear to outcompete zebra mussels, as quagga mussels can colonize to greater depths and are more tolerant of colder water temperatures. Both mussels can clog water intake structures and have negative impacts on recreational activities as a result of sharp mussels accumulating on docks, boat hulls, and swimming areas. They outcompete native freshwater mussels, and also filter plankton out of the water, which depletes it as a food source for other native species. Quagga mussels can reduce water quality as they can increase the presence of toxic algal blooms, which can have health impacts on native wildlife.

Management

The best way to manage quagga mussel populations is to prevent them from spreading, as established infestations are extremely difficult and costly to control. They latch onto boats and can be easily spread between water bodies. To prevent their spread, practice the “Clean, Drain, Dry” protocol on all watercraft and gear. Ensure that all plants, animals, and mud are removed from boats and trailers before leaving an area, and drain all water from your boat, motor, and bait buckets. Watercraft can be decontaminated using a potassium chloride solution (KCl) or by power-washing.

Photo: Amy Benson, U.S. Geological Survey, Bugwood.org -

![]()

Rusty Crayfish

The rusty crayfish (Faxonius rusticus) is an aggressive species native to the Ohio River Basin that has spread to about 20 states and 2 Canadian provinces. Angler bait bucket emptying is thought to be the primary cause of introduction outside of the rusty crayfish’s native range. Rusty crayfish can be identified by the rusty-colored oval patch on the sides of their bodies. The rest of the body is grey-green to red-brown in color, and their claws create a distinctive oval-shaped gap when closed. Rusty crayfish live in freshwater habitats like lakes, rivers, streams, and ponds, and prefer to have cobble and debris to hide under. They reproduce rapidly, with females carrying up to 200 eggs at a time. Rusty crayfish outcompete native crayfish, destroy aquatic plants, alter food webs with their aggressive feeding habits, and even negatively impact fishing by removing shelter and eating the food used by fish.

ManagementThe best way to manage the spread of the rusty crayfish is to avoid using them as bait and to clean, drain, and dry watercraft when traveling to new waterbodies. Boaters and anglers should be sure to properly dispose of unused bait and to check watercraft and gear to ensure that there are no living organisms that may be hitching a ride. Restoring predators like bass and sunfish may also aid in the management of their populations.

Photo: USGS -

![]()

Chinese Mystery Snail

The Chinese mystery snail (Cipangopaludina chinensis) is an invasive snail that is native to Southeast Asia and Eastern Russia. It first appeared in California in 1892 as a food source, and established populations were found on the East Coast by the 1910s. This species is commonly imported and sold by the aquarium trade, and people spread Chinese mystery snails primarily through movement of water-related equipment and release of aquarium pets. Snails hidden in mud and debris may stick to anchors, ropes, scuba, fishing, and boating gear. Their strong “trap door,” called the operculum, allows them to close their shells and survive out of water for multiple days. They grow up to three inches tall and have coiled spiral shells, often light to dark olive in color with 6-8 convex whorls. Chinese mystery snails graze on materials at the bottoms of lakes, ponds, and rivers. They are called "mystery" snails because females give birth to young, fully developed snails that suddenly and mysteriously appear. Once established in a waterbody, they outcompete native mollusks and filter feeders for food and habitat. In large populations, their high filtration rate can lead to water quality issues comparable to those resulting from zebra and quagga mussel infestations. Large die-off events can result in foul smells when they wash ashore, and they can carry and transmit trematode parasites that are found in native mussels.

Management

The best management strategy for Chinese mystery snails is to prevent their spread by cleaning, draining, and drying all watercraft and equipment. Ensure that all plants, animals, and mud are removed from boats and trailers before leaving an area, and drain all water from your boat, motor, and bait buckets. Watercraft can be decontaminated using a potassium chloride solution (KCl) or by power-washing. It is also essential that aquarium snails are never released into the wild. For established populations, manual removal, hydro-raking, and professional application of molluscicides are options, but community education and the prevention of new introductions remain the best strategies.

-

![]()

Round Goby

The round goby (Neogobius melanostomus) is an invasive fish that was introduced to the Great Lakes in the early 1990s through ballast water on ships from the Black Sea. Native to the freshwater region of Europe’s Black and Caspian Seas, they continue to be spread by being transported and dumped from bait buckets and water-containing compartments of boats. They also swim through both natural and manmade waterbodies such as rivers and canals to reach new waterbodies. Round gobies are brownish-gray in color with dark brown or black splotches. During spawning and nest guarding season, males have black bodies with yellowish spots. They can also be identified by their puffy cheeks, raised eyes, and single, fused pelvic fin. They can be distinguished from the native sculpin by the prominent black spot at the base of their first dorsal fin. They are aggressive, reproduce quickly, and have big appetites, allowing them to outcompete and reduce native fish populations, which negatively impacts fishing and tourism industries. They also feed on disease-carrying mussels, which increases the mercury content of sportsfish which consume them and has resulted in botulism outbreaks among native fish and birds. Round gobies further act as a vector for viral hemorrhagic septicemia (VHS), a serious, fatal fish disease affecting many native species.

Management

The best way to manage round goby populations is to prevent them from spreading from one waterbody to the next by cleaning, draining, and drying all watercraft and equipment before visiting new waterbodies. Do not dump aquarium contents near any waterbodies, drainage ditches, and sewers. Anglers should be sure to use certified bait that is non-invasive and disease free, and should learn to identify and report round goby. If a round goby is caught, do not release it. Other management options can be successful depending on the size of the population, such as using traps, dams, canal locks, and electrical barriers to deter movement.

Photo: Center for Great Lakes and Aquatic Sciences Archive, University of Michigan, Bugwood.org -

Asian Carp

Asian carp is a term used to describe four species of invasive carp: the silver carp, bighead carp, grass carp, and black carp. These carp are native to Asia, but were introduced to the United States during the 1970s for aquaculture and to control nuisance algal blooms and parasites in ponds. Within ten years, the carp escaped confinement and spread to the waters of the Mississippi River Basin and other large rivers like the Missouri and Illinois. The Mississippi River system served as a freshwater highway that allowed invasive carp to enter many of the country’s rivers and streams. Carp are prolific feeders, and are in direct competition with native aquatic species for food and habitat. Rapid population increases have disrupted the ecology and food webs of large rivers and have interfered with commercial and recreational fishing. Silver and bighead carp feed on plankton, which is also a key food source for many native juvenile fishes. The silver and bighead carps’ high level of feeding on plankton can have serious impacts on the stability of the food web by eliminating the main food source for native planktivorous fish. Black carp are molluscivores, and could become a threat to rare or endangered clam, snail, and mussel populations, as well as to lake sturgeon, which are also molluscivores. Grass carp feed on aquatic vegetation, but their voracious appetite can destroy aquatic ecosystems, cause algal blooms from excess nutrients, and impact native fish by removing their food and shelter.

Management

Established populations of Asian carp can be difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate. Populations might be minimized in some areas by denying access to spawning tributaries via construction of migration barriers or chemical deterrents, but this can be an expensive endeavor which may also negatively impact native species. Commercial harvesting incentives and early detection with eDNA may aid in population management. The best control of Asian carp is to prevent their introduction into new waterbodies.

-

![Rudd]()

Rudd

The rudd (Scardinius erythrophthalmus) is an invasive fish which is native to Western Europe in the Caspian and Aral sea basins. Bait bucket release is thought to be the primary mechanism of the rudd’s introduction into open waters, but the history of its introduction is complex and only partly known. It was initially brought into the United States in the late 1800s or early 1900s. The rudd is a stocky, deep-bodied fish with a forked tail. It has a distinctive mouth with a steeply-angled protruding lower lip. Its sides are a brassy yellow, tapering to a whitish belly, with bright reddish-orange pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins. Rudd inhabit weedy shoreline areas of lakes and rivers, and can adapt to a wide range of environmental conditions. As omnivores, rudd may compete with native species for habitat and food, such as algae and small invertebrates. Adult rudd can eat large amounts of aquatic plants along shorelines, which can degrade spawning and nursery habitat for native fish such as yellow perch, northern pike, and muskellunge. As hardy, omnivorous fish, rudd may fare better than many native fishes in waters that are eutrophic or polluted, resulting in decreased biodiversity.

Management

The best way to manage rudd populations is to prevent them from spreading from one waterbody to the next by cleaning, draining, and drying all watercraft and equipment before visiting new waterbodies. Since young rudd can resemble baitfish, it is important to drain water from bait buckets, bilges, and livewells before taking boats to new waterbodies. Dispose of unwanted live bait in the trash, never in or near the water. Anglers should be sure to use certified bait that is non-invasive and disease free, and should learn to identify and report rudd. If a rudd is caught, do not release it

Photo: USGS